OSTAP SLYVYNSKY

Ostap Slyvynsky was born in Lviv in 1978. He is a poet, translator, essayist, and literary critic. He authored four books of poetry. He was awarded the Antonych Literary Prize (1997), the Hubert Burda Prize for young poets from Eastern Europe (2009), and the Kovaliv Fund Prize (2013). Slyvynsky coordinated the International Literary Festival at the Publishers Forum in Lviv in 2006–2007. In 2016, he helped organize a series of readings titled “Literature Against Aggression” during the Forum. Slyvynsky’s translations had earned him the Polish Embassy’s translation prize (2007) and the Medal for Merit to Polish Culture (2014). In 2015, he collaborated with composer Bohdan Sehin on a media performance, “Preparation,” dedicated to the civilian victims of war in the East of Ukraine. Slyvynsky teaches Polish literature and literary theory at Ivan Franko National University.

From the Translators

Tatiana Filimonova & Anton Tenser

Hailing from Western Ukraine and bearing the clout of several languages and traditions, Ostap Slyvynsky is a masterful DJ. The storybook structure of his narratives teems with unmistakable realia of contemporary everyday life.

Slyvynsky’s texts are formally simple: there is no overt rhyme or meter, the grammar and lexicon are modestly dressed in the commonplace and common sense. The complexity of the poems comes from the third person narrator, whose voice, for the most part, remains twice removed from the reader. This second degree of detachment from the main pathos is achieved by two complementary strategies.

First, the described events are related to the reader in a mediated fashion. We are separated from them by a movie screen (“Lovers on a bicycle”), a dance performance (“Alina”), or an extra narrator, who either recounts an erstwhile conversation (“Story (2),” “Latifa,” “A scene from 2014”), or embeds oneself unexpectedly into the main narration (“Kicking the ball in the dark”).

Second, each poem’s center of gravity is to be found outside its body. The narratives, as if clandestinely overheard/overseen by the reader and author simultaneously, represent small cross-sections in time that betray a knowledge of larger, possibly catastrophic events that remain outside of our field of vision. Slyvynsky’s power lies in making us believe that these larger, four-dimensional stories really exist beyond the synchronic slice of the poem’s text.

The two axes of detachment act as padding between the reader and the seemingly horrific and tragic events, lest the reader becomes desensitized and averts their gaze. Protected by this fragile armor, we are able to interact with events, feelings, or experiences that are otherwise overwhelming.

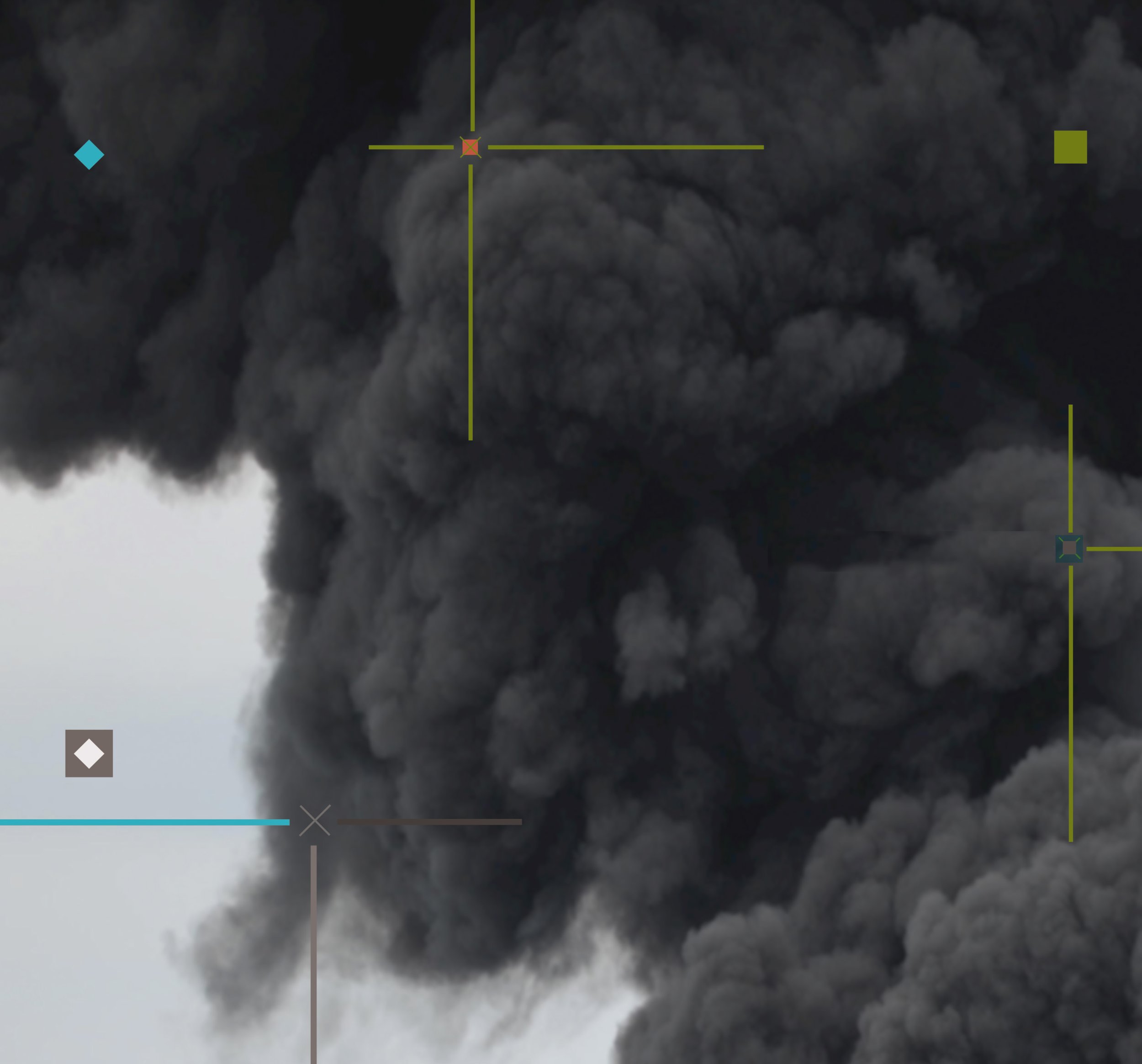

Readers are enticed to make guesses, imagining visions of the greater story. What happened to the miner in 2014, what kind of explosion is at the center of the poem? Why was the house in “Latifa” abandoned -- who left it, when? What is the “whole story” that awaits the “skinny and lost” boy from “Orpheus”? What responsibilities keep the “lovers on the bicycle” apart? We have to take steps to conjure up the events outside the immediate narrative. The magic of Slyvynsky’s poetry is to make us trust that taking these extra steps, making our guesses, is worth our while.